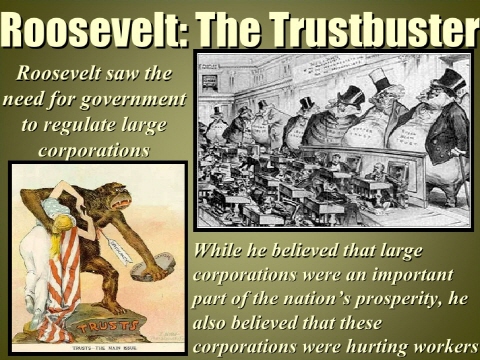

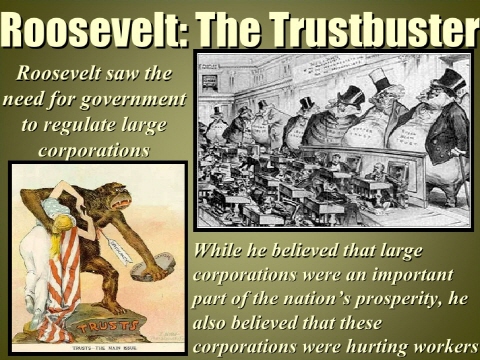

Should the Government Bring Back Trust-Busting?

AT&T’s plan to purchase Time Warner for $84.5 billion faces fierce political opposition — a reflection of the growing suspicion of concentrated corporate power in the U.S. that helped fuel Donald Trump’s presidential win and the upstart success of Bernie Sanders’ primary campaign. Though most similar mergers have passed regulatory scrutiny in the past few decades, many say that this deal may be blocked due to a “revolution in antitrust thinking” that goes beyond this one case. Does the government need to more proactively pursue antitrust cases? Is it time to bring back trust-busting?

* purchase = 구입[구매/매입]하다/ face = (상황에[이]) 직면하다[닥쳐오다]/ fierce = 격렬한, 맹렬한; 사나운, 험악한/ political opposition = 정치적 반대/ reflection = (상태, 속성 등의) 반영/ suspicion = 의심, 불신; 느낌/ concentrated 집중된; 결연한; (물질이) 농축된/ fuel = 부채질하다; 연료를 공급하다/ upstart = 벼락부자, 벼락출세한 사람/ merger = (조직체, 기업의) 합병/ regulatory scrutiny = (산업・상업 분야의) 규제[단속]력을 지닌 정밀 조사[철저한 검토]/ antitrust = 독점 금지[규제]의/ proactively = [사람・정책이] 상황을 앞서서 주도하는, 사전 대책을 강구하는/ pursue = 추구하다, (어떤 일을 어느 정도의 기간을 두고) 밀고 나가다[해 나가다]/ trust-busting = 반(反)트러스트[기업 합동]의 공소(公訴)[정치 운동]

정부는 더 주도적으로 독점금지 사례를 추구할 필요가 있나요? 반트러스트를 다시 도입할 때 인가요?

정부는 더 주도적으로 독점금지 사례를 추구할 필요가 있나요? 반트러스트를 다시 도입할 때 인가요?

1. Monopolies Are Antithetical to Democracy

The proposed AT&T-Time Warner merger is a watershed moment for our political system.

2. Concentration in an Industry Does Not Mean It Lacks Competition

“Big is bad” is perhaps the only thing this year's presidential candidates agreed upon.

Sample Essay

Concentration in an Industry Does Not Mean It Lacks Competition

“Big is bad” is perhaps the only thing this year's presidential candidates agreed upon. Too many big mergers, too little enforcement, goes the narrative.

Left-leaning antitrust commentators have called for an antitrust “revolution.” Even the acting head of one antitrust agency, apparently feeling the strengths of the political winds at her back, declared antitrust “too important to be left to the experts.” The Council of Economic Advisors — a historically reputable outfit no matter the administration — recently released a report blaming increasing market concentration for higher prices and reduced economic growth.

This argument suffers from two fatal flaws. First, it ignores the economically simple — yet often forgotten — truism that a high level of concentration in an industry simply does not mean the industry lacks competition. Concentration and competition are distinct concepts.

Sometimes a concentrated industry is noncompetitive. Consider hospitals, where the Federal Trade Commission has successfully challenged proposed mergers with convincing economic evidence that greater concentration would lead to increases in price and reduced quality of service.

Conversely, an industry with two or three firms can be more competitive than one with 50, such as supermarkets or online platforms like Uber where economies of scale can enhance competition between fewer but healthier players. The last 40-plus years of economic research is clear: Simply counting the number of firms in an industry tells you very little about competition.

The new antimerger fervor is based upon the presumption that they are never a good deal for consumers because more consolidation always leads to higher prices, and never leads to cost savings or product improvements that benefit consumers. Both are demonstrably false. Antitrust agencies close the majority of their merger investigations precisely because the proposed deal offers no threat to competition or to the benefit of consumers.

What's more, the evidence that supports the conclusion that markets are actually becoming more concentrated is exceptionally weak. The Council of Economic Advisors concluded that we have a monopoly problem because, in a handful of industries, the combined market shares of the top 50 firms have seen a modest increase over the past few decades.

But a closer look shows that the council found that the combined market shares of the top 50 firms is below 50 percent in nearly all industry sectors. The average market share for a firm in these industries is less than 1 percent. That is certainly not evidence of a monopoly problem.

Economists have long rejected the “antitrust by the numbers” approach. Indeed, the quiet consensus among antitrust economists in academia and within the two antitrust agencies is that mergers between competitors do not often lead to market power but do often generate significant benefits for consumers — lower prices and higher quality. Sometimes mergers harm consumers, but those instances are relatively rare.

Because the economic case for a drastic change in merger policy is so weak, the new critics argue more antitrust enforcement is good for political reasons. Big companies have more political power, they say, so more antitrust can reduce this power disparity. Big companies can pay lower wages, so we should allow fewer big firms to merge to protect the working man. And big firms make more money, so using antitrust to prevent firms from becoming big will reduce income inequality too. Whatever the merits of these various policy goals, antitrust is an exceptionally poor tool to use to achieve them. Instead of allowing consumers to decide companies’ fates, courts and regulators decided them based on squishy assessments of impossible things to measure, like accumulated political power. The result was that antitrust became a tool to prevent firms from engaging in behavior that benefited consumers in the marketplace.

The antitrust agencies are full of talented economists and lawyers who use the most up-to-date and sophisticated techniques to identify mergers worthy of challenge on behalf of consumers. Economic analysis has more often than not trumped ideological politics in antitrust policy for the past 35 years. Let’s keep it that way.

![]() 정부는 더 주도적으로 독점금지 사례를 추구할 필요가 있나요? 반트러스트를 다시 도입할 때 인가요?

정부는 더 주도적으로 독점금지 사례를 추구할 필요가 있나요? 반트러스트를 다시 도입할 때 인가요?